Good Times with Random Weapons

Good Times with Random Weapons

Playing games with your friends should be the best way to play. Usually it’s the worst.

This is counterintuitive because doing anything with your friends is much more fun than doing it alone, so what do I mean? Usually you are having fun because you are in a shared space with your friends rather than because you are having the same type of fun that a single player game brings to the table. I go to single player games for pattern recognition, exploration, and personal improvement and there are many ways in which the simple fact of having another person in the same virtual world as you undercuts those core drives.

The ways that we force the humans involved in a game to interact largely determine how much fun they will have, what conflict they will engender between each other and if they will actually grow as players. You don’t learn to build a cathedral by watching a mason lay bricks, you must move the stone yourself, and cooperative games can get in the way of that.

I am fascinated by what makes some games tilting/toxic while others engender community and fun and I think it usually comes down to a few questions: Are players on the same team competing for resources? Can a 99th percentile player and a 20th percentile player exist in the same game without ruining the experience for the other? Is there a way to clearly delineate responsibilities? Is griefing possible or encouraged?

Co-op Mode

Minecraft, being the quintessential forever game gets more of this right than wrong. While griefing is a real issue in that game, for the most part the fun of a Minecraft server is working on a shared project together with friends. But, if we look at the play patterns most common on YouTube for Minecraft we see a few through lines.

Many of the SMP YouTube channels will work on their own builds and projects in a separate area from the other players on the server and only occasionally interact directly with their peers in the same place and time. Often they are interacting together closely in space and may extend previous projects from other members of the server, share building resources etc. Striking that balance between group and individual play styles is what makes Minecraft really work.

In Minecraft we have an infinite world so no fighting over resources, player directed goals so the player’s responsibility is what they want it to be, and an easy way for the 99th percentile player to exist in the same world as the 20th: feel like you aren’t contributing to the main project? just hop a few chunks over and start your own. There is a ton of griefing though, no game is perfect.

On the other hand there is the Minecraft speedrunning community that has invented a game, Minecraft Speedrunning Ranked (MCSR), that has all of the hallmarks of the competitive shooter, fighting game, or RTS genres with leaderboards, ELO, and a whole sequence of evolving meta strategies. This side of the community is definitely more toxic than the building side, but less toxic than games of similar size that have direct competition in their game play. In MCSR game you are racing against an opponent and will gain or lose ELO depending on whether you beat the game faster than them, but there is no possibility of griefing or moment to moment competition since you are not in the same persistent world as your opponent.

I have also seen way less Disconnects in that gamemode than you might expect in for example fighting games. I think this is because the touch points where you can know if you are doing poorly or well are very low fidelity. You might see that your opponent is ahead of you in the speedrun, but you only get updates on their progress when they achieve a major milestone. There is also always the possibility that they might die or otherwise fail the run, so a good player should always finish their matches. On the other hand if you are playing a fighting game like Melee, if there is a large or even medium sized skill gap it is quite clear who will win the match within the first minute and every failed maneuver, damage taken, or stock lost is a painful reminder of that inevitability.

Even in a solely cooperative PvE experience, skill gaps or game design can still get in the way of a good time. My Brother and I used to play a lot of Civilization V in high school and we’d always play as allies. For the most part this worked because each of our Civs would start out somewhat far away from each other and we could focus on conquering our immediate neighbors until the end game where we’d team up against the last civ left standing.

One place where the cooperation broke down was around decisions where there is an objectively correct choice. For example much of what to research was like this, there is usually one good tech in the tech tree that will unlock the next bottleneck to expansion and we should both be researching it. To not coordinate on that would be foolish and that’s probably why you see the AI teams fall behind.

Another place where the design of the game limits how much you can cooperate is around expansion itself. If one of the players takes all of the cities in the direction of the remaining enemies, they effectively block their teammate from getting more cities. Then, the player far from the action becomes increasingly less and less relevant going into the end game. Their supply lines are longer and they will take fewer cities in the future. Without constant expansion, your economy flounders and your Civ contributes less to World Domination. This can be circumvented by the players themselves, but requires planning on their part.

In competitive online shooters like CS:GO, playing with your friends is very fun but unless all of the group commits to regular practice and games together there will be a wide variation in skill levels of the lobby. Some of the more competitive players will be annoyed at losing more than they would alone and the less skilled players will be annoyed by constantly fighting teams of much higher ELO than they can handle. This isn’t the fault of the matchmaking, both the carry and the carried necessarily have to be placed incorrectly to find a match at all.

Solo queueing flattens the skill gap of your team, but at a price. You have to play with strangers who have very low investment in your team doing well, working together well socially, or even communicating at all. For the most part your team will be full of people who after 90 minutes will never see each other again.

Thinking of Dark Souls multiplayer, each player’s world is distinct and a player cannot pick up items in another player’s world so there are limits to how much you can help each other. The multiplayer aspects while still fun are fairly weak. Skill gaps still lead one of the players to get carried or carry. Bosses are mostly designed for singleplayer so a weak player will run away and wait for their buddy to kill the boss circumventing all possibility of challenge or learning.

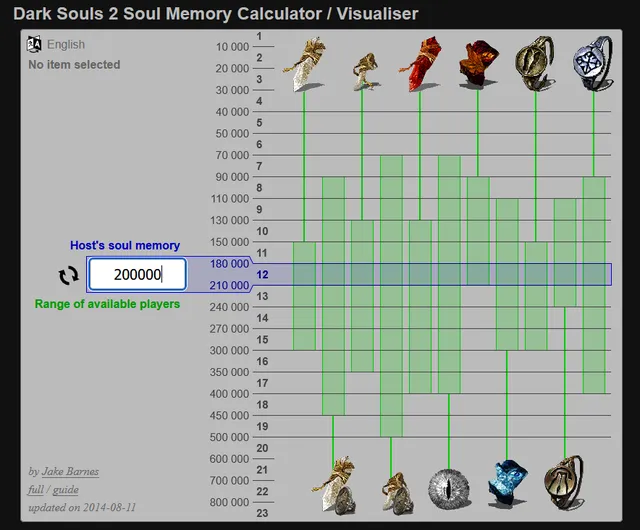

Dark Souls 2 attempted to fix this through Soul Memory so that a player could only match with other players within a similar level range to them. This introduced a whole host of other problems: mainly that an experienced player on a fresh save file will still carry you during a summon or kick your ass during an invasion. It also makes it almost impossible to reliably match with your friends. Dark Souls 3 further refined the system by having anyone be able to connect on a password system. The game would then scale down the summoned player’s stats and health to roughly match the host. Again the issue was that even with really terrible stats a good player can still carry most encounters. At least to me it seems like all of the attempted fixes have been band-aids on an unfixable issue that players in the same world with different skill levels must contribute unequally, often in a way that makes the moment to moment gameplay less rewarding than in singleplayer.

Elden Ring: Nightreign, the biggest attempt at true multiplayer in the Souls genre, gets the macro structure right. Players explore, gather drops, and kill minibosses independently until the Act boss forces them back together. That rhythm, separate then converge, is exactly the pattern that works in Minecraft. But in practice, players in Night Reign largely stick together as a group, moving from camp to mines to castle as a warband. The open world is scaled for the full party, so splitting off means fighting encounters tuned for three players alone. The cost of going solo is too high, and so the game collapses back into the same problem: everyone in the same space, skill gaps visible, the weaker players trailing behind the stronger ones.

The Shape of Good Cooperation

So why does Minecraft work so well to engender fun and community where these other games fail to inspire the same level of positive passion? I think it comes down to three factors.

First, a shared cooperative goal to bring people together. The Minecraft server has a communal project, Civ V has a shared enemy, the Act boss in Night Reign forces convergence. Without a shared goal the players are just alone in the same room.

Second, the freedom to separate without penalty. This is the critical one. Minecraft’s infinite world means you can walk a few chunks away and build at your own pace. Nothing punishes you for being alone, but also nothing prevents you from cooperating more directly. In Civ V, each player has their own territory to manage. In CS:GO you’re somewhat independent holding site and taking names, but every time you get domed you let your friends down and boy does that feeling suck. In Night Reign, you can’t meaningfully separate, and that’s where the experience breaks down. The cost of going solo has to be low enough that players of different skill levels can each operate at their own peak without being forced into the same encounter.

Third, ways to help each other without taking over. Sharing resources, extending a friend’s build, sending items between worlds. These are touchstones that keep players connected without one player doing the work for another. Being carried is no fun and carrying is somewhat fun, but if you want your friends to actually improve or learn the mechanics of the game then maintaining a distance is important. Similar to mentorship, it requires people to understand where each other are at and what to improve from there.

This is what I thought a few years ago: Co-op games are hard and couch co-op is long dead. There are a few games like Minecraft that really get how to get people to work together instead of pit players against each other. But then I found Archipelago.

I’m sure you’ve seen the videos, but for those who haven’t Archipelago is a system that connects games together in a multi-game randomizer. What this means in practice is that a key that I need to beat The Legend of Zelda could be hidden somewhere in Dark Souls, or Hollow Knight, or any one of a few hundred games. When we start we pick what games we want to play, and then the goal is for each individual player to complete their game, all the while they are finding items to send to other players in their lobby.

At first the appeal might seem simple. The idea is shallowly attractive because there are so many games in the catalogue that are nostalgic and were world class games in their own time. I definitely think that is part of the appeal, but I think there is something more here because of a counterintuitive reason: it is so hard to setup! When players jump through hoops to set something up, there is unmet demand in the gaming market.

I have worked on the Dark Souls I Archipelago randomizer and just understanding how to contribute to it took a few hundred hours in Ghidra looking at the game’s memory and decompiled assembly code. Long weekends spent figuring out how to modify the game’s memory when the Archipelago server sent items to the player. Reverse Engineering how the Dark Souls item pickup menu worked, how to change out the item pickup text in a way that wouldn’t break the game and decoupling the item portrait display from the item received in the player’s inventory.

And that’s just on the developer’s side, for a player to setup a world they need multiple computers networked together, and each game’s randomizer has a set of custom instructions, often with undisclosed edge cases, for setting up just that world. Usually for me, and I went to school for Computers, it takes a few hours the night before to setup a new roster of games and make sure everything’s working. Partially that is because my friends and I want to play some of the games that are not in the main list and so are in different states of working, but also it is just a really complicated project to setup.

But all of that headache is worth it, cause when all of your friends are in the same room and working toward one goal it really is fun.

By splitting players up more directly, each player can choose a game they are good at and can operate at their individual peak skill level, all while still contributing to the group’s success. Then the game and social dynamics become more like a company than a warband. We agree on some goals and how we are each going to contribute, and then we go do that. The little touchstones along the way: sending items between worlds and sharing game knowledge keeps us connected without forcing us into the same space.

But Archipelago as an open source project can’t become a platform on its own. Each new game in the roster requires hundreds of hours of reverse engineering to integrate, and the project scales linearly with developer labor. More fundamentally, the entire system works by modifying game binaries and memory that the project has no legal right to distribute commercially. Every supported title is one DMCA notice away from being pulled. A purpose-built platform with its own games sidesteps both problems: no reverse engineering bottleneck, no legal fragility, and developers build for the platform rather than hacking around existing games.

The Next Generation of Forever Games

When looking for startup ideas, loosely defined as ideas that can improve the world, instantiated in a company to make the ideal real, it is important to look for the ways that people are acting abnormally. Most people want their life to be simple and convenient, so when they add great amounts of complexity to their lives it is important to ask, what need is not being served by the market here?

Riot is the best example of this: they took a mod of a game that had very poor multiplayer experience and turned it into a billion dollar company. I wasn’t allowed to play internet games at the time but here is just a short list of some of the hurdles players jumped through at the time:

-

You needed Warcraft III to be on Frozen Throne 1.20c patch

-

Warcraft III would automatically update to the latest version on Battle.net, but new patches broke the map or third-party tools.

-

Players had to use “Version Switchers,” unauthorized programs that hacked their game files to downgrade from version 1.24 back to 1.20 or 1.21 just to enter a lobby.

-

If you and the host weren’t on the exact same patch, you couldn’t see the game.

-

There were no accounts or penalties so people were constantly DCing when something went a little wrong.

-

The community maintained “Ban lists” literal text files that tracked usernames of known match leavers.

-

All of this was done through server lists with filters in the lobby name for region and skill level with no ELO or matchmaking

Despite all of this around 2009–2010, IceFrog (the lead developer of the mod) estimated the game had between 7 to 11 million active players. Even though there was an insane level of friction, the demand was clearly there and Riot capitalized on it.

Riot took DoTA (a content innovation that there was clear demand for) cloned it and added a distribution innovation on top of the mod by adding the free to play business model. Riot was the first to bring F2P to the West in a time when videogames were still sold in large boxes mainly through physical retail stores. Completely skipping the normal distribution routes allowed them to move faster than Blizzard. For their part Blizzard did not clone DoTA until ~6 years after League came out with Heroes of the Storm. Even though all of assets aside from the game mode itself were Blizzard’s, they could not move as fast as Riot especially since most of their profits came from WoW subscriptions and big budget games like Diablo and StarCraft. The lead in asset generation and platform development that Riot had allowed them to clone Blizzard’s infrastructure and siphon off much of their community and bought them a ticket to become a Major studio.

Ideally a gaming company does not try to chase hit games. This is somewhat unintuitive because what is any company aside from its hits? The answer lies in distribution advantages. Why are Sony, Nintendo, Microsoft, and Valve Majors while other companies struggle? At least in part it is because for a few generations Sony, Nintendo, and Microsoft had the distribution advantage of determining what was published on their console hardware. Steam being the other main publishing avenue has captured the distribution advantage for the internet age, taking a 30% cut of virtually all PC games by owning the pipes that sell games. More recently Riot and Minecraft have both had distribution advantages over their competitors.

Minecraft took a content innovation (virtual Legos) and through the growth of YouTube, created a sustained distribution advantage. When I was a kid Minecraft videos were the main form of content on YouTube and that is still true today. This is mainly because of the moddability of the platform and the ability for storytelling in the blocky world. When you give players the ability to create anything, they can do as many parodies of other media as they like and the game developer is not liable for the infringement (note that Roblox maintains the same ambiguity in their moderation and succeeds for many of the same reasons).

Notice the flow that allows an Indie to become a Major: a small content innovation with clear unfulfilled demand, maintained by a sustained distribution innovation. Far too many indies focus on the content side of things, answering the question of: how do I make a hit game? when what actually matters is the ecosystem that allows your games company to be an actual company rather than a payout mechanism for a single product.

The content innovation is straightforward: build games that are designed from the ground up for multi-world cooperative play. A purpose-built system would skip all of Archipelago’s friction and let players get to the good part: each person in their own game, contributing to a shared goal, growing at their own pace.

The distribution innovation is what turns that into a company. Once the tools for creating sub-games are opened to users, every new game mode and art asset that anyone builds adds value to the entire ecosystem. This is the same flywheel that made Minecraft and Roblox durable: players create content, that content attracts more players, and the platform captures the network effect. The difference is that in an Archipelago-style ecosystem, user generated games do not have to thrive on their own. A new game doesn’t split the player base, it enriches it, because your friends don’t have to play the same game as you to play with you.

That last point is the real unlock. Every multiplayer game today forces the friend group to converge on a single genre and a single skill curve. Archipelago decouples what you enjoy playing from who you enjoy playing with. If you pair that with a free to play model and a shared cosmetic marketplace across sub-games, you have the bones of a forever game and a sustaining games business.